Das BRYTER-Event

Juni 30, 2021

PwC Legal x JUST Legal Tech – Der Einsatz von Legal Tech im Arbeitsrecht

September 11, 2021

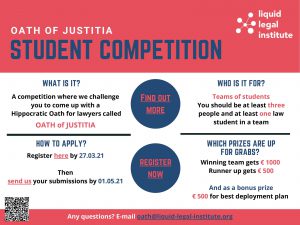

Our Entry for the “Oath of Justitia Competition” by the Liquid Legal Institute

By Karl Björn Erlemann, Sven Graf & Dana Celine Berger

Introduction

Today, the Hippocratic Oath is recognized in many countries as a cornerstone of medical ethics. Written in antiquity, it still serves as a guide for physicians across the world today and has embedded principles such as ‘do no harm’ within the profession.

The Liquid Legal Institute (LLI) asked: What would a similar oath look like for lawyers? How should an Oath of Justitia be formulated? In the modern digital world, should it be different from an oath written in Ancient Greece, and if so, how?

Our version of an Oath of Justitia took into consideration six main areas of tension, that is,

- The balance between the lawyer as an agent of the administration of justice and as a businessperson

- The relationship between their role as one-sided representative to their duty towards society

- The difficulty of unifying the pluralistic profession under a uniform oath

- The balance between moral and freedom of practice

- The quality of practice under special consideration of the commercialisation, specialisation, interprofessionality and technologization of the profession

- The balance between honesty and confidentiality

From our perspective, the main role of the lawyer comes down to their service to laypersons. Choosing this as the guiding principle, we came to the portrait of a lawyer, that stands out as a free and independent legal counsel, bound by human rights and the rule of law, but free to seize economic opportunities and technological developments for the best of the layperson.

Oath of Justitia

I commit, to the full extent of my capacities and judgment, to the following statements and shall endeavour to reach towards the ideal they represent:

(1) I shall practice freely and independently, only limited by the standards set in this oath.

(2) I shall practice for the good of my client within the boundaries of human rights and the principles of democracy.

(3) I shall respect my responsibility as an agent in the administration of justice and shall not contradict the ethical standards that it demands regarding my activity in the legal market.

(4) I shall maintain confidentiality and integrity about clients’ concerns and am unreservedly discreet. Trust is the currency and basis of the relationship between lawyer and client.

(5) I shall advise to the best of my knowledge and belief. All clients are equal before the law and before my quality standards – irrespective of the case to be handled and its financial relevance.

(6) I shall not refrain to cooperate with different professional groups in order to find truth.

(7) I shall ensure that my knowledge is sufficient to guarantee correct advice. My advice shall always be guided by the boundaries of the law and the needs of citizens seeking justice.

I solemnly take this oath, freely and on my honour.

Explanation of our version of an “Oath of Justitia”

Explanation for the introduction

While the full commitment to the contents of the oath and their perfect application would be ideal, it is not only an unrealistic expectation but also contradicting the first section of the oath (“I shall practice freely and independently”)[1]. As you need to account for human imperfection, we added the line “to the full extent of my capacities and judgment” and used the word “endeavour” regarding the realization of the ideals that the oath sets.

Explanation for Section (1)

Freedom and independence are considered to be some of the core values that describe the profession of lawyers.[2] It is obviously contradicting to talk about “freedom” on one side and “only limited by…” on the other. There is indeed the valid argument that “freedom” can only be achieved through the intrinsic moral of the individual and the homogeneity of the group, as the extrinsic protection by regulation of freedom abolishes freedom itself (known as the “Böckenförde-Dilemma”).[3] In consideration of the specialisation of the legal profession within the past few decades (the “classical” court lawyer was joined, if not replaced by, highly specialised consultants, inhouse-counsellors and in the last few years even legal technology firms disrupting the standard practice of legal counsel), it is important to recognize that the interests and motives within the profession differ, thus diversifying moral standards.

While Hellwig rejects the codification of ethical standards for lawyers[4] mainly because of the dilemma mentioned above, we think that for exactly that reason a codification is required. Therefore, we added the appendix “only limited by the standards set in this oath”. As seen below, we restrict the sources of morality and ethical guidelines to the core element that everyone in the profession shares, that is, the lawyer’s role to guide laypersons. Obviously, this flexibility allows for ambiguity in interpretation of the standards. However, we think that this needs to be accepted to take all variants of the profession into account.

“Independence” in this context means the absence of control or pressure by authorities, the public or because of a subordinate status in the firm[5]. This shall ensure that lawyers are able to fulfil their duties as mentioned in the introductory sentence “to the full extent of their capacities and judgment”. The independence of lawyers is an integral part of their role to give access to justice for laypersons. The layperson only has the chance to receive justice if lawyers are unobstructed in their freedom of practice. The independence of lawyers is not only important for the factual enforcement of someone’s rights, but also plays a symbolic role for lawyers as a person of trust for the layperson. Independence, however, has its borders in the self-organization and regulation of lawyers by themselves to ensure the quality of the practice.

Explanation for Section (2)

Section (2) sets the objective and boundaries of the lawyer’s practice. Today’s lawyers can be seen from three perspectives[6] that may or may not conflict with each other:

- The lawyer as the representative and consultant of their client

- The lawyer as an agent of the administration of justice

- The lawyer as a businessperson and service provider

We think that the lawyer’s role as representative and consultant of their client should be his main role, before his role as agent of the administration of justice and most definitely before his role as a businessperson. Of course, lawyers should be profitable in exercise of their practice. But if lawyers rank profitability over their duty towards the client, they cannot fulfil their intended purpose to give access to justice and therefore become obsolete. On the other hand, their intended purpose as agent of the administration of justice shall not go beyond what giving access to justice means. It is not the lawyers’ job to balance diverging interests of parties but the judges’ job. A lawyer should be neutral when consulting to be able to give the client the appropriate consultations and recommendations, but should be one-sided in court to enforce the clients’ rights in the client’s interest.

Additionally, the phrase “for the good of the client” should also be interpreted as what is in the best interest of the client and not necessarily what is potentially legally possible. This dogma can be found in a variety of guiding principles for legal professionals, for example in the “Solicitors Regulation Authority” (SRA) code.[7] The purpose of lawyers always leads back to guiding laypersons. Therefore, we want to emphasize the possibility for lawyers to centre their service around the needs of the layperson, as the upcoming trend of Legal Design suggests. With the phrase “for the good of the client”, we want to allow and encourage the use of technology, if it is contributing to the objective of guiding the layperson.

With the phrase “within the boundaries of human rights and the principles of democracy” we want to give the exercise of practice a clear boundary. A lawyer shall not give consultancy on how to avoid the enforcement and realization of human rights or how to hide their infringement. Furthermore, lawyers shall not help to undermine democratic principles such as the rule of law.

Explanation of Section (3)

Our opinion that a lawyer’s main role is the representation and consultation of the client shall not exclude the other two perspectives from being taken into consideration. For obvious reasons, the role of lawyers as agents of the administration of justice is an integral part of the profession as well. The lawyer profession is characterized by societal interests and public welfare. In line with this concept of public service, the legal profession is even privileged concerning certain legal tasks to ensure the quality of practice and the functioning of the system. Lawyers are required to be truthful and shall not mislead the client or the court. Therefore, we chose the words “respect the responsibility”. It is the lawyers’ duty to abide by the law and support its enforcement. The ethical standards that this role entails are

- Honesty, in the regard that the lawyer is practicing for the good of the client,

- Competency, in the regard that the lawyer is proficient in the exercise of the profession

- and Justice, as the desired outcome.

With the phrase “regarding my activity in the legal market” we want to exclude practices that do not support the client’s interest, do not ensure the quality that the layperson trusts or do not pursue the goal of achieving justice. We consider practices, in which a lawyer is not helping the client to enforce their rights, but merely actively looking for cases with the sole intent of self-enrichment, not only as malicious to the system but especially malicious to the reputation and trust towards other lawyers. When lawyers are making up cases to justify their existence, they act immorally.

However, this shall not prevent lawyers from being active as businesspeople. Therefore, we refrained from further restrictions in a separate section in the oath in regard to economic activities. It is the lawyer’s freedom to do business, enhance their services or diversify into different markets. As we consider that a freedom of practice, a special section in the oath was not considered to be necessary.

Explanation for Section (4)

The lawyer-client relationship must be characterized by mutual trust. This is the only way to ensure the ideal counsel and representation of interests. Trust requires that two people meet on a level where they do not have to fear being exposed or betrayed. Especially in the context of law, there is a threat of social ostracism and discrimination if sensitive information leaks out. However, the lawyer must know the whole truth in order to be armed in court and to be able to represent the client in the best possible way.

Confidentiality must be unrestricted in order to provide the security required to demand unconditional trust. Breach of confidentiality may only be considered in cases in which disclosure is needed to preserve a high legal interest. In all other cases, the lawyer must respect the attorney-client privilege and make it the most important maxim. It is the lawyer’s duty to create the preconditions for a confidential exchange of information. This specifically includes consultation via digital mediums.[8] A moral and ethical conflict must be decided in favour of confidentiality.

Explanation for Section (5)

The quality of counselling must always be maintained at a consistently high level. This is justified by the fact that people are equal before the law. No one may be favoured or disadvantaged. This circumstance maintains social trust in the legal system, which is essential to ensure a functioning constitutional state. The question is whether a lawyer is a capitalist entrepreneur or a benefactor. The answer to this question is neither black nor white. A balance has to be struck between profit and pro bono work. Making a living is just as understandable an interest as assuming social responsibility and also advising those who are not wealthy.

To guarantee a high level of quality, lawyers need to keep up to date with current legal developments, specifically new legislation, judgments and academic discussion.

Explanation for Section (6)

The lawyer cannot be expected to be a specialist in all areas. In different proceedings, the advice of different specialists must be sought. To find the truth, a multi-perspective view is necessary. It is one of the necessary skills to work together on a matter in order to exhaustively fathom and fully understand it. Only the truth enables proper legal advice.

Explanation for Section (7)

Only those who can demonstrate professional expertise are in a position to give correct legal advice. The modern lawyer finds himself in the area of conflict between expertise and generalism. Neither the generalist nor the specialist can be classified as superior. Legal advice cannot be divided into valuable and worthless. What is decisive is correctness. Specialist knowledge in this context is merely a means to an end and it is not important whether the lawyer is specifically a lawyer for everything or a specialist lawyer for certain areas of law.

The lawyer as part of the administration of justice is the person who is closest to the citizen and also represents his interests before the state or the court. The quality of his advice can be measured by whether the client feels that the legal framework was used in such a way that justice could be done.

[1] More to this in the explanation for Section (1) of the oath.

[2] e.g. No. 14 and 16 of the “Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers”, adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, 1990; Principle I, Nr. 1 of “Recommendation of No. R(2000)21 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the freedom of excercise of the profession of lawyer.

[3] Hellwig, “Berufsrecht und Berufsethik der Anwaltschaft in Deutschland und Europa”, Tübingen 2015, p.287 ff.

[4] Hellwig, “Berufsrecht und Berufsethik der Anwaltschaft in Deutschland und Europa”, Tübingen 2015, p. 295 ff.

[5] See Loughrey, “Corporate lawyers and corporate governance”, Cambridge 2011, p. 52 f.

[6] Wagner, “Vorsicht Rechtsanwalt!: Ein Berufsstand zwischen Mammon und Moral, München 2014, p. 282.

[7] Sec. 3.1 in the SRA Code of Conduct for Solicitors, RELs and RFLs.

[8] See Wagner, “Vorsicht Rechtsanwalt!: Ein Berufsstand zwischen Mammon und Moral, München 2014, p. 55 f.